How To Fix A Loose Snap Button

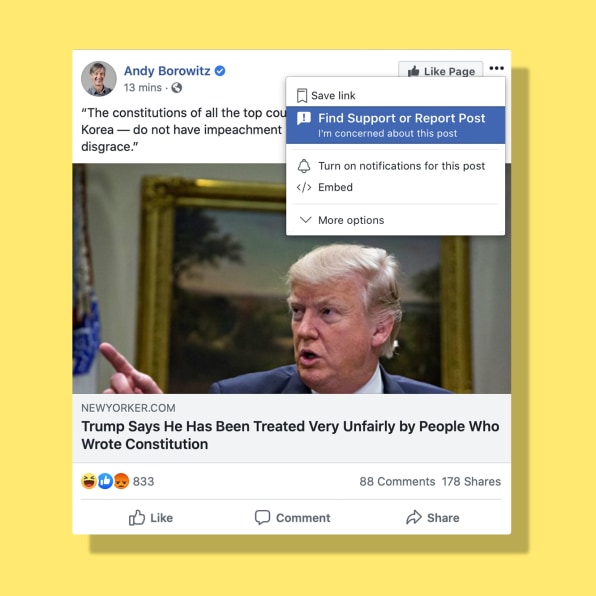

"Trump Sees New Polls and Orders Ukraine to Investigate Elizabeth Warren." "Obama to Produce Netflix Serial About Trump's Impeachment." Like everything "comedian" Andy Borowitz writes for The New Yorker, these headlines aren't specially funny, even if yous spot the "joke." Simply they are, technically speaking, satire. That is, until they appear on Facebook, and as yous curlicue chop-chop on your feed, where they are nearly duplicate from actual fake news.

(In example yous wonder if people are confused, go ahead and google "The New Yorker height stories." The search engine's first "People also ask" result is, "Is the New Yorker real news?" Yes . . . information technology's bad.)

To The New Yorker'south slight credit, it'south taken steps to more clearly label these stories as "satire." And according to new research out of Ohio State Academy, published in the Journal of Calculator-Mediated Communication, Facebook should place overt labels on all satirical stories that announced in its feed. Considering information technology found that whereas we tend to cringe at and debate the veracity of "fake news," we all agree upon the fiction of "satire."

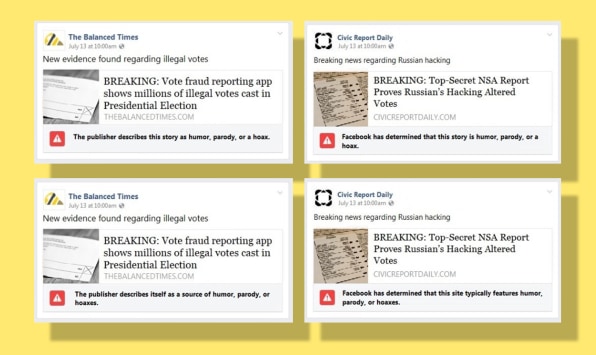

The paper presents two studies, run with hundreds of participants. Each was given a simulated version of their Facebook feed and told it was real and based upon their browsing. The first compared the efficacy of Facebook'due south "disputed" flags that it was using to fact check news articles in 2016 with a simpler "satire" label. What researchers plant was that the "disputed" flags didn't appear to piece of work at all in convincing someone something was false. Merely calling it satire did.

In fact, when Republicans were shown a fake story about Democrats voting twice, they reported to "somewhat hold" on average when information technology was flagged as disputed but reported to "somewhat disagree" when it was labeled satire. On the opposite terminate of the political spectrum, when Democrats were shown a fake story near Russian hacking, they also reported to "somewhat agree" when it was flagged as disputed and "somewhat disagree" when it was labeled as satire.

"We are confident that the difference is non the product of take chances," says OSU professor and lead writer Kelly Garrett.

A second study compared how that satire label might work more than specifically, as in, would it exist more than effective if Facebook labeled a story as satirical, or the publication itself called the story satire? Would people trust the decision more than or less depending on the source? Researchers constitute no deviation. As long as it was flagged satire, people got the indicate every bit.

As Garrett puts it, the solution here is incredibly simple for Facebook (and whatsoever other news aggregator, for that matter) and can be worked into their interface. "I think labeling things equally satire is such a straightforward solution," says Garrett, who points out that the research found there's really nothing to lose. "The humor of satire is not grounded in fooling someone. Satire isn't less funny just because someone tells yous it's satire. Y'all're not harming the satire, and you're potentially helping the people who might be fooled."

Just, if the satire label works and then well, might information technology make sense for Facebook just to label all simulated news as satire?

When I pose the question to Garrett, he walks me through Facebook's arroyo to imitation news thus far. He points to the way Facebook has labeled imitation stories with the message "this story has been disputed by . . . "

"[That's] an interesting selection of words. It's intentionally, I call back, Facebook'due south endeavour to avoid being an arbiter of truth," he says. "It [also] risks having false equivalence." Garrett's point is that in not choosing a side on arguments, punting to third-political party fact checkers, and labeling stories "disputed" rather than simply "false," Facebook had basically mirrored the fashion climate coverage used to work. The media would present both "sides" of the argument every bit when, in reality, the science is indisputable. In brusque, Facebook's flagged arroyo (which ended in 2017; Facebook has since announced exploring vague, new initiatives), simply opened the door to fake equivalence.

Equally for labeling all faux news equally satire—a fib, possibly, just a fib in the name of people believing the truth —Garrett cautions against information technology. "We have to exist careful not to abuse the label. We don't desire to start labeling stuff not intended as satire as satire, because then audiences would rightly exist suspicious of the label," he says.

In any case, he admits that disinformation, like organized propaganda of foreign governments, is a rampant trouble that transcends whatsoever "silver bullet" solution. Just satire, information technology appears, is a rare, easy set for social media.

"I call back information technology's great; we should take satire. It's a useful form of advice," says Garrett. "[But] satire shouldn't come at the price of actually agreement the political surround. "

How To Fix A Loose Snap Button,

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90415320/the-button-that-could-fix-one-of-facebooks-biggest-problems

Posted by: harisowayll.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Fix A Loose Snap Button"

Post a Comment